Running From Arthritis?

Abundant data is proving that running does not cause or exacerbate osteoarthritis in healthy subjects. (1-10) In fact, some studies have shown that running may help to prevent joint degeneration. (8-11) However, running does not necessarily impart the same protective benefit to the entire kinetic chain. Studies show that one-year lower extremity injury rates for distance runners may reach an astonishing 79%. (12,13) This stat is supported by our own clinical experience and the fact that very few first-time marathoners ever run again competitively.

The good news is that running-related injuries are often preventable. Check out this blog/video that will arm you with the knowledge to help your runners recover and stay injury free. As a bonus, you can download our new running infographic to share with your patients and social media followers.

Here’s what the research tells us about the relationship between running and arthritis:

Long-distance running is not associated with accelerated radiographic knee arthritis in the absence of knee injury, obesity, proprioceptive deficit, or poor muscle tone. (1-5)

A prospective longitudinal study of long-distance runners suggests that overall disability levels in runners increase with age at 25% of the rate of more sedentary controls. (6,7)

Whereas other exercise increased osteoarthritis and hip replacement risk, running significantly reduced their risk due, in part, to running’s association with lower BMI. (8)

Arthritis prevalence was 8.8% for marathoners, significantly lower than the 17.9% prevalence in the matched U.S. population. (9)

Regular weight-bearing exercise, (i.e., running) helps prevent cartilage degradation by suppressing the release of PGE2 inflammatory molecules that cause pain and stiffness. (10)

Long-term running is associated with better IVD hydration and proteoglycan content. (11)

However, running has a less attractive side too. Studies show that one-year lower extremity injury rates for distance runners may approach 79%. (12,13) Here are three tips that you can employ today to help your runners heal and stay injury-free.

1. Choose the Correct Shoe Style

In general, you can predict the most suitable running shoe based upon the outline that would be created on the pool deck by a wet foot.

If your outline looks like a full-width foot, you probably need a motion control shoe to help control an overpronating arch. This shoe is designed for people with low or no arches. Avoid overly stiff motion control shoes as they decrease your perception of ground strike and can lead to new injuries.

If you leave an outline that has a “skinny” midfoot, then a cushioned shoe may be your best choice. This shoe is designed for people with high arched feet. This shoe is more flexible and absorbs the shock created by the lack of pronation.

And if you don’t fall into either of the two extremes, then a stability or neutral shoe is your likely choice. This shoe is designed for people with normal arches and running mechanics. The shoe contains some cushioning to absorb shock and prevent injuries and some rigidity to avoid pronation.

* Regardless of your shoe style, running shoes should be replaced every 250 miles.

2. Avoid the Terrible Too’s

All too often, athletes suffer from the “terrible too’s”- they train too much, too hard, and too fast. Injuries develop or return when runners attempt to develop their bodies too fast. Our phasic and postural muscles need to be activated slowly to build capacity and performance.

Increasing mileage significantly beyond current tissue capacity leads to detrimental compensations. (14)

The 10-percent rule is one of the most important and time-proven principles in running. It states that someone should never increase their weekly mileage by more than 10 percent over the previous week. For example, if your patient is running 10 miles one week (5 runs @ 2 miles per run), they should only increase their total distance to 11 miles the next week. This gradual increase in activity allows their body to adapt to the progressive demands.

3. Practice Good Form

For clinical edification and humor, attend a local 5K and observe the plethora of faulty running mechanics. Identifying and correcting all of these biomechanical faults is not possible; however, there is one piece of advice that sticks out most: Avoid the dreaded crossover gait.

Many runners will “run on a line” with an excessively narrow gait. This may be the effect (and perpetuator) of hip abductor weakness, as athletes plant their support at midline - beneath their center of gravity. This narrow gait is compensation for hip abductors that are not strong enough to maintain stability and pelvic balance if the foot was planted at normal width.

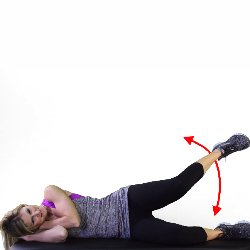

Strengthening exercises that target the hip abductors, particularly the gluteus medius, may help improve mechanics and minimize injuries. Here are a few examples.

In contrast to the familiar training axiom, practice does not always make things perfect, but it does make them “permanent.” Teach better running form by asking the athlete to maintain a three-inch gap between their feet during the stance phase in gait, i.e. straddle a line. This can be a tough task, so start with short distances and slowly increase by ten percent per week..

-

Chakravarty EF, Hubert HB, Lingala VB, Zatarain E, Fries JF. Long distance running and knee osteoarthritis. A prospective study. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(2):133–138.

Cymet TC, Sinkov V. Does long-distance running cause osteoarthritis?. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 2006 Jun 1;106(6):342-5.

Bijlsma JWJ, Knahr K. Strategies for the prevention and management of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee.Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007;21:59–76.

Felson DT. An update on the pathogenesis and epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Radiol Clin North Am. 2004;42:1–9.

Lo GH, Driban JB, Kriska AM, et al. Is There an Association Between a History of Running and Symptomatic Knee Osteoarthritis? A Cross-Sectional Study From the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017;69(2):183–191.

Wang BW, Ramey DR, Schettler JD, Hubert HB, Fries JF. Postponed development of disability in elderly runners: a 13-year longitudinal study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2285–2294.

Lane NE, Oehlert JW, Bloch DA, Fries JF. The relationship of running to osteoarthritis of the knee and hip and bone mineral density of the lumbar spine: a 9 year longitudinal study. J Rheumatol. 1998;25:334–341.

Williams PT. Effects of running and walking on osteoarthritis and hip replacement risk. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(7):1292–1297.

Ponzio DY et al. Low Prevalence of Hip and Knee Arthritis in Active Marathon Runners. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018 Jan 17;100(2):131-137.

Fu, S. et al. Mechanical loading inhibits cartilage inflammatory signalling via an HDAC6 and IFT-dependent mechanism regulating primary cilia elongation. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, Volume 27, Issue 7, 1064 - 1074

Belavý DL et al. Running exercise strengthens the intervertebral disc. Scientific Reports. 19 April 2017

Hoeberigs JH et al. Factors related to the incidence of running injuries. A review. Sports Med. 1992 Jun;13(6):408-22.

van Gent RN, Siem D, van Middelkoop M, van Os AG, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Koes BW. Incidence and determinants of lower extremity running injuries in long distance runners: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41(8):469–480.

Koblbauer IF, et al. Kinematic changes during running-induced fatigue and relations with core endurance in novice runners. J Sci Med Sport. 2014.