Can Chiropractic Care Help with Chronic Ankle Sprains?

Reading time: 5 minutes

A recent paper by Picot et al. (2022) demonstrated the importance of including patient-reported ankle function questionnaires, traditional orthopedic testing, and functional tests to identify patients suffering from chronic ankle sprains (CAI). While these tests may sound time-consuming, this blog will give you the skills to provide all three of these assessments for CAI within seconds. The second half of the blog will provide the most up-to-date evidence supporting treatment techniques and rehabilitation exercises you can use in your office to help manage these patients.

Lateral ankle sprains (LAS) are the most common injury in an athletic population. While most patients resume daily life after an ankle sprain, up to 40% of individuals who experience a first-time LAS will develop chronic ankle instability. (1) CAI causes several adverse effects. These patients will suffer reduced quality of life, diminished ankle functionality, predisposition to future ankle sprains, and an increased incidence of post-traumatic osteoarthritis of the ankle. (2)

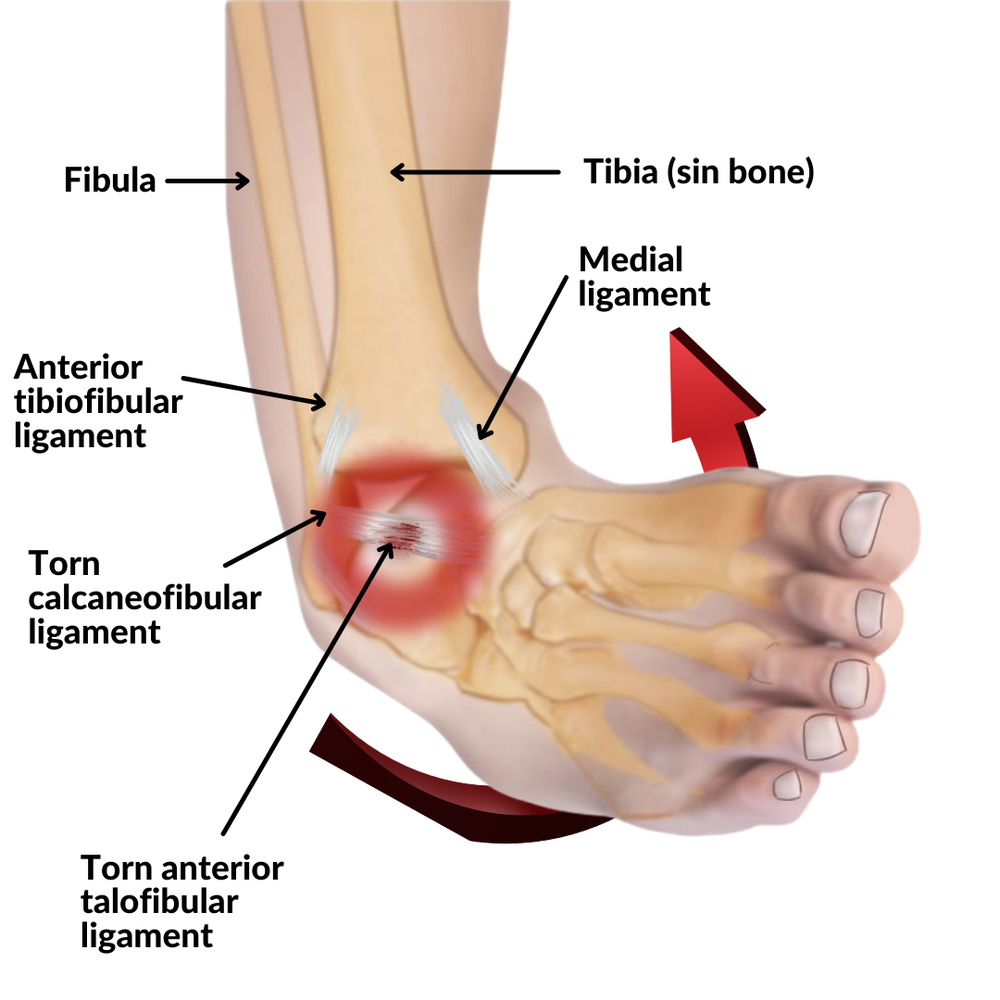

Ankle sprains commonly affect the passive ligamentous structures on the lateral aspect of the ankle joint: the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL), the calcaneofibular ligament (CFL), and the posterior talofibular ligament. These ligaments are exposed to injury when the ankle positioning includes forefoot adduction, hindfoot inversion, external rotation of the tibia, and ankle plantar flexion. The ATFL is the most common ligament injury, with an overall incidence of 70%. (3)

For rehabilitation and prognosis purposes, it is crucial to understand the severity of ankle sprains.

Grade I: mild ligament stretching without joint instability.

Grade II: a partial rupture with mild joint instability.

Grade III: a complete rupture of the ligament complex with ankle instability.

Clinical Presentation/ Assessment

The most common symptoms associated with chronic ankle instability are pain, swelling, a feeling of giving away, or weakness upon activity. (4)

The FADI and FADI Sport may provide objective measurements of the disability. These two reliable instruments:

Allow providers to detect functional limitations in subjects with CAI

They are sensitive to differences between healthy subjects and subjects with CAI

Measure response to the improvement in function after rehabilitation. (5)

If you don’t like asking your patients 34 questions found within the FADI. Consider the Functional Ankle Instability Index. It is less reliable in isolation but has only six questions with a positive relationship between functional ankle instability and performance deficits on the side hop and figure-of-8 hop. (6)

Orthopedic Evaluation

Traditional orthopedic evaluation of ankle sprains includes various stress tests to challenge ligamentous integrity. Reproduction of pain or lack of a firm endpoint when passively stressing a joint suggests ligamentous injury. Specific tests include the Talar tilt test (Inversion stress test) that is performed with the ankle in neutral to challenge the CFL, with variations in plantar flexion and dorsiflexion to test the ATFL and PTFL, respectively. The Anterior Drawer Test may be positive in anterior talofibular ligament involvement cases. (10) The Posterior Drawer Test and the Anterolateral Drawer and Reverse Anterolateral Drawer Test may also help define the presence of instability.

Functional Evaluation

Gluteal muscle weakness is a risk factor for sustaining lateral ankle sprains. (Check out the Hip Abductor Weakness protocol in ChiroUp) Performing the Single Leg Stance Test or the Single Leg Squat Test may help elucidate dysfunction in hip stability. (7) To evaluate ankle stability and the ability to return to play measurements, the Side Hop Test and Square Hop Test (8) are useful in assessing the functional ability of patients suffering from chronic ankle instability.

The patient begins standing on the affected leg. The patient jumps from side to side over two parallel strips of tape placed 30 cm apart on the floor. The examiner will count a successful hop after the patient jumps over the line and back. If the patient touches the tape, the hop doesn't count. The patient will perform the hops as fast as possible for 1 minute. The number of successful hops is recorded and used to measure patient progress.

The patient begins standing next to a 40×40-cm square marked on the floor with tape. Participants hop in and out of the square as fast as possible for five repetitions. One repetition includes hopping in and out of the tape outline on each of the four sides. [With the right limb, participants hopped in a clockwise direction, and with the left limb, they hopped in a counterclockwise direction.] The time required to complete the test will demonstrate progress during a treatment plan.

Chiropractic Management of CAI

Current management of CAI targets deficits in proprioception, reduced balance, loss of ankle range of motion, and changes to muscle strength extending into the entire lower kinetic chain. (2) Populations of patients with CAI also demonstrate altered hip and knee kinematics during dynamic tasks.

Joint manipulation (HVLA) to the ankle with resistance exercises is synergistically effective in improving the ankle pain intensity, ROM, and balance ability. (9) Ankle manipulation is effective in patients with subacute and chronic ankle sprains. (10)

Manual therapy may also be used in exercise-based rehabilitation to improve patient-reported outcome scores in patients with CAI. (11)

Semirigid bracing and kinesiotaping are also helpful for improving balance in patients suffering from CAI. (12)

Rigid bracing with an Aircast may also be beneficial for acute pain; however, rarely used for long-term use.

Rehabilitation Strategies for CAI

Exercise Therapy

Exercises therapy serves two significant purposes in the rehabilitation of patients with CAI. These patients require progressive loading of injured tissue and training to improve balance. (13) CAI patients often lack proper foot stability and balance resulting in increased lateral loading of the foot. (14)

Balance Training

Single leg stance exercises are beneficial to both improve foot stability and strength. Balance training on one foot benefits the affected and unaffected sides. (18) Once the patient can balance on one leg for 30 seconds, eyes open; consider having the patient close their eyes for another 30 seconds removing one source of proprioception to challenge postural stability further. Patients may also consider resistance bands, wobble boards, and hopping exercises for post-acute injuries: once they achieve full ankle range of motion and a single leg stance of 30 seconds. Rehab duration is often 3-6 months beginning in the office and slowly transitioning to at-home exercise plans.

Bracing

However, in players without a previous ankle sprain, the use of an ankle brace did make a significant difference in two of the braced groups. The Active Ankle Trainer II and the Aircast Sports Stirrup protected volleyball players from a sprain only if they had not had a previous sprain. If the player had a history of a previous ankle sprain, these two brace groups did not protect the ankle from another ankle sprain (p < 0.05). (19)

CAI is a challenging diagnosis, as many patients have biomechanical and psychological compensations built around ankle instability. I would love to hear from you on other strategies you have used in your office to help these tricky cases.

To learn more about ankle sprains and 115 other diagnoses, check out the clinical skills section in ChiroUp. Thank you for letting our team help keep you up-to-date to get the best clinical results for your patients. If you have any suggestions:

Please email me at brandon@chiroup.com

Click on the megaphone on the top right of the home screen of ChiroUp.com.

Not yet a subscriber? Get started now for FREE.

-

Hertel J, Corbett RO. An updated model of chronic ankle instability. Journal of athletic training. 2019 Jun;54(6):572-88.

Owoeye OB, Whittaker JL, Toomey CM, Räisänen AM, Jaremko JL, Carlesso LC, Manske SL, Emery CA. Health-related outcomes 3-15 years following ankle sprain injury in youth sport: what does the future hold? Foot & Ankle International. 2021 Aug 5:10711007211033543.

Dhillon S, Adhya B, Rajnish RK, Dhillon H, Dhillon MS. Lateral Ankle Sprain: Current Strategies of Management and Rehabilitation Short of Surgery. Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery (Asia Pacific). 2022;9(1).

Anandacoomarasamy A, Barnsley L. Long term outcomes of inversion ankle injuries. British journal of sports medicine. 2005 Mar 1;39(3):14.

Hale SA, Hertel J. Reliability and Sensitivity of the Foot and Ankle Disability Index in Subjects With Chronic Ankle Instability. J Athl Train. 2005;40(1):35-40.

Docherty CL, Arnold BL, Gansneder BM, et al. Functional-performance deficits in volunteers with functional ankle instability. J Athl Train. 2005;40:30–4.

DeJong AF, Koldenhoven RM, Hart JM, Hertel J. Gluteus medius dysfunction in females with chronic ankle instability is consistent at different walking speeds. Clinical Biomechanics. 2020 Mar 1;73:140-8

Caffrey E, Docherty CL, Schrader J, Klossner J. The Ability of 4 Single-Limb Hopping The Functional Performance Deficits in Individuals With Functional Ankle Instability. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39:799–806.

Shin HJ, Kim SH, Jung HJ, Cho HY, Hahm SC. Manipulative Therapy Plus Ankle Therapeutic Exercises for Adolescent Baseball Players with Chronic Ankle Instability: A Single-Blinded Randomized Controlled Trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020 Jan;17(14):4997.

Nield, S.; Davis, K.; Latimer, J.; Maher, C.; Adams, R. The effect of manipulation on range of movement at the ankle joint. Scand. J. Rehabil. Med. 1993, 25, 161–166.

Walsh BM, Bain KA, Gribble PA, Hoch MC. Exercise-based rehabilitation and manual therapy compared with exercise-based rehabilitation alone in the treatment of chronic ankle instability: A critically appraised topic. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation. 2020 Jan 7;29(5):684-8.

Hadadi M, Haghighat F, Mohammadpour N, Sobhani S. Effects of kinesiotape vs soft and semirigid ankle orthoses on balance in patients with chronic ankle instability: a randomized controlled trial. Foot & Ankle International. 2020 Jul;41(7):793-802.

Kosik KB, McCann RS, Terada M, et al. Therapeutic interventions for improving self-reported function in patients with chronic ankle instability: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2017;2017(51):105–12.

Hertel J, Olmsted-Kramer LC. Deficits in time-to-boundary measures of postural control with chronic ankle instability. Gait Posture. 2007;25(1):33–9.

Shin HJ, Kim SH, Jung HJ, Cho HY, Hahm SC. Manipulative Therapy Plus Ankle Therapeutic Exercises for Adolescent Baseball Players with Chronic Ankle Instability: A Single-Blinded Randomized Controlled Trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020 Jan;17(14):4997.

Wright CJ, Linens SW. Patient-reported efficacy 6 months after a 4-week rehabilitation intervention in individuals with chronic ankle instability. J Sport Rehabil. 2017;2017(26):250–6.

Kim T, Kim E, Choi H. Effects of a 6-week neuromuscular rehabilitation program on ankle-Evertor strength and postural stability in elite women field hockey players with chronic ankle instability. J Sport Rehabil. 2017;26(4):269–80.

Elsotohy NM, Salim YE, Nassif NS, Hanafy AF. Cross-Education Effect of Balance Training program in Patients with Chronic Ankle Instability: a randomized controlled trial. Injury. 2020 Oct 1. Link

Frey C, Feder KS, Sleight J. Prophylactic ankle brace use in high school volleyball players: a prospective study. Foot & ankle international. 2010 Apr;31(4):296-300.